Operationalizing Equity: Measuring Digital Health Access, Literacy, and Outcomes

Dr. Christopher K. Gransberry is a Faculty Member at Purdue University Global, which is a current HIMSS Approved Education Partner.

Summary

Digital health is revolutionizing care delivery, but unless care is delivered with a well-developed measurement infrastructure, digital health promises to amplify disparities. With the rise of digital options, such as telehealth and mobile apps, as critical parts of the equation of health access, marginalized communities still suffer uneven access, literacy, and uptake. Even as much national attention comes to health equity moving forward, a specific leadership gap remains unsatisfied: no coherent evidence-based health equity measurement tool exists to measure digital health equity.

This article aims to propose a Digital Health Equity Measurement Framework (DHEMF) that would convert intention into action. The framework is divided into three domains: Digital Access, Digital Literacy and Privacy, and Digital Use Health Outcomes. It offers measurable, stratifiable metrics to health systems, payers, policymakers, and health IT professionals. It is guided by new studies and targeting the lapses in implementation, data infrastructure, and evaluation. The DHEMF is trying to drive fair digital transformation through the healthcare system by standardizing equity benchmarks and making them part of organizational strategy.

The stakeholders have to be united by a common vision: a vision where successful digital health is not only innovative but inclusive. Digital health has the potential to be a tool of justice, as opposed to a mechanism of inequality, with data-driven planning and partnership across multiple fields.

Introduction

Although the digital transformation of healthcare is rewriting the dynamics of access to care, digital inclusion has not come to fruition. The possibilities to limit disparities in health outcomes, such as telemedicine, patient portals, wearable devices, and mobile apps, are greater than ever. However, digital advances may reinforce the historical disparities among regions and groups without strategic equity metering, particularly low-income and rural, elderly, and racially minoritized strata (Kaihlanen et al., 2022; Pritchett et al., 2023).

Federal programs have started mitigating such lapses. The Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ONC) has prioritized interoperability standards to capture social determinants of health (SDoH), and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) has made health equity measures a requirement of value-based care incentive programs. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has ensured health equity within its data modernization and surveillance systems. Together, these efforts indicate an increment in the observance of justice in implementing digital health.

Nevertheless, momentum is not enough. The big challenge still stands: no standardized, measurable indicators can be applied to determine whether digital tools are reasonably available and comprehensible, with their usage delivering evident results within populations. In numerous health systems, the challenge is that people are unaware of how digital solutions will work across races, languages, disabilities, ages, and geographic lines (Petretto et al., 2024).

This lack of strategy-and-measurement collusion leaves a vacuum of leadership. Although inclusion, accessibility, and justice are touted as values, very few organizations have a data infrastructure that enables them to turn those intentions into accountability. Digital health equity is not merely a matter of digitizing; it is the framework that clarifies what is supposed to be done, how it is going to be measured, and how it can be adapted in real time.

The emergence of this gap has prompted scholars and practitioners to establish models that encompass implementation science and the principles of digital equity (Groom et al., 2024; Richardson et al., 2022). Measurement cannot stop at typical population rates but must shift to stratified evidence that explains disparities and intervention evidence. Otherwise, we are likely to scale digital tools to ensure the most vulnerable are left out systematically.

If we are to redefine and measure success to create health equity in the digital world, we should reconsider the health inequities and disparities to improve the problem. Digital equity must not be looked at as a retroactive concern, but as an active design tenet. This is how to shape the future of equitable healthcare based on whether we are practical and able to develop, implement, and refine the metrics, which are inclusive as the care we provide.

Defining the Gap

Although the issue of digital disparities is widely recognized, no commonly agreed-upon framework exists that can be used to gauge the level of digital health equity. Without standardized measures, organizations cannot assess interventions, equitably redistribute resources, or address other population-based aspects of improvement (Park & Jang, 2024). This disconnect kills accountability and restricts the capacity of effective practices to scale. It also repeats its blind spots in strategy, in which digital instruments can function well at an aggregate level and fail among marginalized user groups. A consistent measurement model is missing, as otherwise, health systems may maintain inequitable tendencies in the name of innovation.

The Digital Health Equity Measurement Framework (DHEMF)

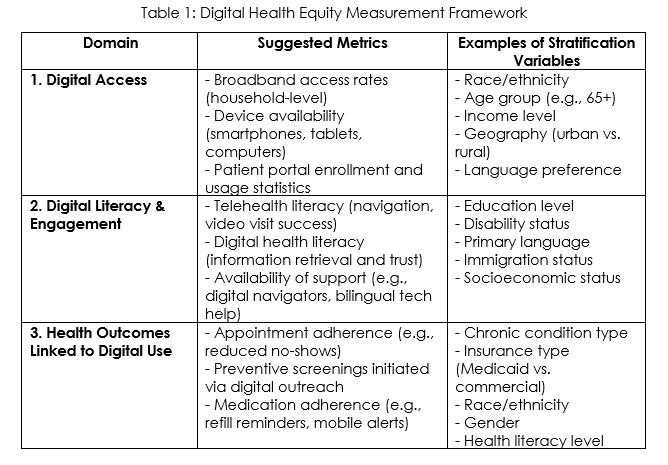

To bridge the gap between digital innovation and health justice, we present the Digital Health Equity Measurement Framework (DHEMF), an evidence-based, strategic, evidence-informed model that is expected to enable the empowerment of healthcare systems to track and develop digital equity. The framework has its background in implementation science and health informatics, along with digital health equity scholarship, and provides actionable metrics in three areas that rely on each other: Digital Access, Digital Literacy & Engagement, and Health Outcomes Linked to Digital Use (Groom et al., 2024; Richardson et al., 2022).

Table 1 summarizes the DHEMF, which organizes actionable metrics into three interrelated domains - Access, Literacy & Engagement, and Health Outcomes, while emphasizing the importance of stratified data collection across key equity variables. These domains provide a blueprint for designing and evaluating equity-centered digital health strategies across diverse populations.

1. Digital Access

Digital access is described as people's underlying ability to access digital health services. Other components of digital health equity cannot be carried out without this foundation. This area entails:

- Broadband access: A measure taken as a percentage of patients with a stable connection to high-speed internet at home.

- The rate of access to internet-enabled devices like smartphones, tablets, or even computers: The percentage of people with access to internet-ready technologies.

- Patient portal enrollment and usage: The rate of portal activation and login, and the rate of portal messaging activities by demographics.

The geography (urban vs. rural), race/ethnicity, income, language, and age disaggregation of these measures should be provided. As an example, the level of broadband coverage can look adequate on the aggregate level but hide a wide range of gaps within marginalized populations. Kaihlanen et al. (2022) stated that older adults, immigrants, and low-income groups continued to experience access barriers in the COVID-19 era, such as restricted digital infrastructure and ownership of digital technology.

Stratification of the access measures can help health systems understand where investments in infrastructural projects or subsidies might be needed. If broadband penetration is 85% within a population and 60% for low-income seniors, then obviously, there is a digital divide that needs policy and operational attention.

2. Digital Literacy & Engagement

Being able to access it does not mean it can be used. Digital health tools must be user-friendly, maneuverable, and respond to the users' literacy level and communication needs. In this area, there is a capturing of:

- Telehealth literacy: The skills patients possess to traverse virtual platforms, successfully have video visits, and read care instructions.

- Digital health literacy: The role in which an individual knows how to determine the degree of trust and views on efficiency to search and obtain pertinent digital health-related information.

- Navigational assistance: Access to and the availability of community navigators, web literacy instruction, bilingual technical help, or other relevant sources of support.

The literacy measurements must be reported using patient-reported experience measures (PREMs), focus groups, or usability analyses. Groom et al. (2024) assert that co-designing digital health interventions among marginalized groups is essential to strengthening the intended outcomes in usability and equity. In the same way, Park & Jang (2024) educate the use of ecological strategies that consider not just personal knowledge but also environmental and systemic disincentives to engagement.

Organizations need to measure literacy stratified by language, status of disability, level of education, and socioeconomic status. For example, immigrant populations might be affected by some language issues that cannot be solved by simply providing multilingual portals without any actual time constraints or culturally pertinent interfaces.

3. Health Outcomes Linked to Digital Use

The benefits of a fair digital transformation are better measurable results and improved health outcomes. The sphere links an online interaction with a health outcome:

- Appointment adherence: the capability of reducing the number of no-shows through a digital reminder or self-scheduling tool.

- Preventive screening: A specific screening (mammogram or colonoscopy) that is scheduled or received with the help of a digital nudge or portal outreach.

- Medication adherence: The patient's use of medication and medication management, refill reminders, or text support programs.

There is a need to measure the implementation of digital health tools, as argued by Richardson et al. (2022), but they should also be assessed on their differentially impactful nature. Assuming that improved outcomes with remote blood pressure monitoring are specific to White patients but not Black or rural ones, organizations will have to examine how engagement, literacy, or cultural responsiveness might be subpar. Petretto et al. (2024) also observe that multi-level causal pathways, such as technological-level, levels of individuals, and levels of systems, require integration into equity-focused systems of evaluations.

Cross-Domain Integration and Data Stratification

Each domain must incorporate stratified data collection per race, income, age, geography, disability status, and language. This can provide live equity audits and facilitate actionable information regarding operational enhancement. Minimization of stratification is also consistent with federal equity efforts to promote quality improvement initiatives such as HEDIS and value-based care vignette reviews (Groom et al., 2024; Petretto et al., 2024).

By incorporating equity-based digital health initiatives into organizational dashboard performance, quality committees, and diversity and inclusion initiatives, stakeholders can move past the ad hoc representation of outcomes with structured and long-lasting performance.

Implementation Strategy

Some systems might already be implementing digital equity activities, but the majority are still not in full-blown measurement models. It is advisable to use a phased implementation approach. Health systems are encouraged to test the DHEMF in certain locations where there are Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs), Medicaid accountable care organizations, or community-based telehealth centers.

Working with local public health agencies, digital inclusion nonprofits, and academic researchers can expedite this process. Notably, equity metrics should be programmed in electronic health records (EHRs), performance management systems, and reporting systems to hold institutions accountable (Pritchett et al., 2023). The framework must be adopted to achieve sustainability and become part of the organizational DNA.

Call to Strategic Action

Healthcare leaders must translate long-term vision into evidence-based digital equity when the goal is to achieve. The DHEMF sets a framework for implementing equity in digital strategy, assessment, and design. These measures should be included in the dashboards, performance evaluation, and published statements by health systems, policymakers, and tech vendors. This multisector collaboration (public health, academia, nonprofits, and industry) is the only way to co-create, iterate, and scale the framework. Equity has to be made a collective responsibility, and it is time to measure now.

References

Groom, L. L., Schoenthaler, A. M., Mann, D. M., & Brody, A. A. (2024). Construction of the digital health equity-focused implementation research conceptual model-bridging the divide between equity-focused digital health and implementation research. PLOS Digital Health, 3(5), e0000509. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11111026/

Kaihlanen, A. M., Virtanen, L., Buchert, U., Safarov, N., Valkonen, P., Hietapakka, L., ... & Heponiemi, T. (2022).Towards digital health equity-a qualitative study of the challenges experienced by vulnerable groups in using digital health services in the COVID-19 era. BMC health services research, 22(1), 188. https://research.aalto.fi/en/publications/towards-digital-health-equity-a-qualitative-study-of-the-challeng

Park, N. Y., & Jang, S. (2024). App-based digital health equity determinants according to ecological models: scoping review. Sustainability, 16(6), 2232. https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/16/6/2232

Petretto, D. R., Carrogu, G. P., Gaviano, L., Berti, R., Pinna, M., Petretto, A. D., & Pili, R. (2024).Digital determinants of health as a way to address multilevel complex causal model in the promotion of Digital health equity and the prevention of digital health inequities: A scoping review. Journal of Public Health Research, 13(1), 22799036231220352. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/22799036231220352

Pritchett, J. C., Patt, D., Thanarajasingam, G., Schuster, A., & Snyder, C. (2023). Patient-reported outcomes, digital health, and the quest to improve health equity. American Society of Clinical Oncology Educational Book, 43, e390678. https://ascopubs.org/doi/10.1200/EDBK_390678

Richardson, S., Lawrence, K., Schoenthaler, A. M., & Mann, D. (2022). A framework for digital health equity. NPJ digital medicine, 5(1), 119. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41746-022-00663-0